Timestepping¶

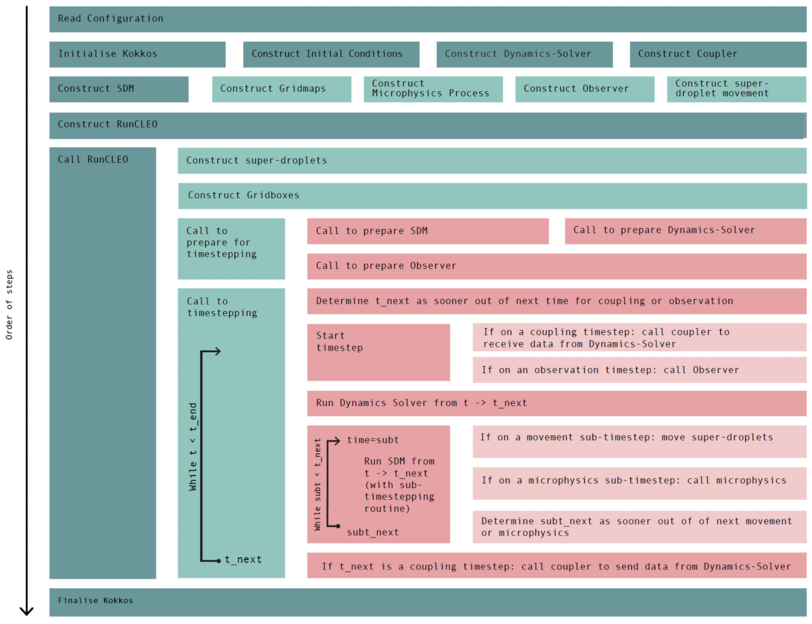

The core elements of Cleo’s routine calling is summarised below.

A schematic for the order of Cleo’s routine calling. Steps on the same level can be executed in any order. A change in colour indicates the steps to the right-hand side are nested within the differently coloured step to its left-hand side.¶

The important part of Cleo’s routine calling occurs in the timestepping loop within the timestepping call of RunCLEO. Here the timestep taken by the model is adapted to always satisfy the timestep of the coupling and observations. Similar adaptive-timestepping logic occurs during the sub-timestepping loop for SDM, ensuring the individual timestep for each microphysical process and for superdrolet motion are all satisfied whilst also ensuring the largest possible sub-timestep is chosen at each step.

Both the timestepping routine and nested sub-timestepping routine for SDM work with timesteps that are in general non-integer multiples of one-another and non-constant values. The only constraint is that all the sub-timesteps of the SDM processes are at least as short as the (outer-level) timesteps for coupling and observations.

The basic idea is as follows…

We define C++ concepts so that any type we use for an “action” (coupling/observations/superdroplet motion etc.) is a type which will obey certain rules that enable our timestepping algorithm to work. This looks a bit like so:

#include <concepts>

template <typename A>

concept Action =

requires(A p, unsigned int t, Gridboxes g) {

{ p.run_step(t, t, g) } -> std::same_as<Gridboxes>; // function enacting some process only on specific timesteps

{ p.next_step(t) } -> std::convertible_to<unsigned int>; // function determining how long until next run_step call

{ p.on_step(t) } -> std::same_as<bool>; // function returning true if the current timestep is when action should be taken

};

Then we can combine these “action” types in an adaptive timestepping algorithm, e.g.

#include <concepts>

...

template <Action Dynamics, Action Microphysics>

void timestep_cleo(const unsigned int t_end, const Dynamics &dynamics,

const Microphysics µphysics)

{

...

auto t_mdl = 0;

while (t_mdl <= t_end)

{

const auto t_next = start_step(t_mdl, dynamics, microphysics);

gbxs = dynamics.run_step(t_mdl, t_next, gbxs);

gbxs = microphysics.run_step(t_mdl, t_next, gbxs);

t_mdl = proceed_to_next_step(t_next);

}

}

where

#include <concepts>

#include <algorithm>

...

template <Action A, Action B, ...> // add more actions here

unsigned int start_step(const unsigned int t_mdl, const A &a, const B &b)

{

...

auto step_a = a.next_step(t_mdl);

auto step_b = b.next_step(t_mdl);

return std::min(step_a, step_b); // add more actions here

}

unsigned int proceed_to_next_step(const unsigned int t_next)

{

...

return t_next;

}

An example of a type which could be an “action” is a microphysical process (like condensation/evaporation) which has a constant timestep. That could look something like this:

...

class ConstantIntervalMicrophysics

{

private:

unsigned int interval = 10;

...

Gridboxes do_microphysics(const unsigned int t_mdl, const unsigned int t_next, Gridboxes &gbxs) const

{

... // here is where microphysical process is modelled e.g. SDM condesation/evaporation

return gbxs;

}

public:

unsigned int next_step(const unsigned int t_mdl) const

{

return ((t_mdl / interval) + 1) * interval;

}

bool on_step(const unsigned int subt) const

{

return subt % interval == 0;

}

Gridboxes run_step(const unsigned int t_mdl, const unsigned int t_next, Gridboxes &gbxs) const

{

if (on_step(t_mdl))

{

gbxs = do_microphysics(t_mdl, t_next, gbxs);

}

return gbxs;

}

};